When lists of the most important individuals in the history of cinema are created, one regular omission is particularly striking.

D.W. Griffith, Georges Melies, Edwin Porter and Alice Guy are frequently referenced as innovative film-makers from the early years of cinema, a group who are credited with creating the medium’s grammar. Similarly, the Lumiere Brothers, Thomas Edison and Louis LePrince are all noted as masterful technicians whose scientific invention created the possibility for movies as an art-form to exist in the first place. One man, however, managed to successfully straddle the divide between artist and technician and, in turn, is perhaps the most talented individual in all of film yet, bizarrely, is often left out of discussions of important film-makers.

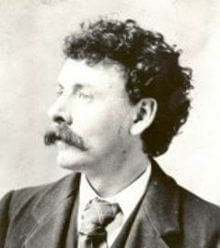

Yet, fewer people deserve the term “film-maker” more than George Albert Smith. Not only did he create some of the most astounding films of the early years of cinema, he also composed much of the technology used by himself and others for years to come. He is a man responsible for inventing parallel action, the non-POV close-up shot, the purposeful de-focus and many other editing techniques we take for granted today. On top of this, Smith also created Kinemacolor – the first working, and widely available, method of filming and screening movies in colour. Without George Albert Smith, it’s possible that the art-form we know and love today may have never have matured, have flourished, and it could easily have become regarded as a novelty, a cheap circus attraction.

One of the first examples of moving images with any artistic integrity comes in the form of G.A. Smith’s Santa Claus which he directed in 1898. The plot is simple, but the magic is not – viewed over 100 years later, it’s impossible not to be touched to the very core with the wonder on display in the film. In the same way young hands will find the most simple of toys mesmerising when touched for the first time, there is a real innocence and enthusiasm in G.A. Smith’s film – it’s a short movie which is full of imagination and discovery, the type of which will never again be experienced in cinema.

The tale is rather simple. One Christmas eve, two children are put to sleep by their mother who switches off the lights. Soon after we can see through the darkness that Santa Claus is making his way down the chimney; he appears in the sleeping child's room and places presents in their stockings. Before the children can awake Santa vanishes (via the use of jump cut) leaving behind only his gifts and two children who, when they return from slumber, are filled with glee.

Played out with the use of double exposure (which Smith had already used in his films The Mesmerist and Photographing a Ghost), Santa Claus is the earliest known example of parallel action in all of cinema. At the time this technique was truly ground-breaking and, although it may now appear rather simple, Smith's bravado directing was awesomely daring in its sophistication when Smith composed it.

There’s an incredible child-like joy in this film; Santa Claus, indeed, is a monument to imagination – not just a child’s belief in Father Christmas, but in Smith’s ability to see things which had never previously existed. Using force of will, Smith took a film camera, a piece of equipment which, lest we forget, was invented entirely for scientific documentation and had only recently been used to film “fiction”, and created an instrument of wonder, something magical. For any fan of cinema, or indeed anybody who believes that, alongside empathy, imagination is the greatest gift human beings are born with, Santa Claus is a real goose-bump inducing piece of cinema and a perfect example of why G.A. Smith should be the top of all lists when it comes to the most important film-makers in history.

Click below to watch George Albert Smith's full film:

No comments

Post a Comment