"Well," I can imagine a muttering agent replying as he tries his best to hide the beads of nervous perspiration gathering on his brow, "the character doesn't really have a character per se, in fact you have less than three lines of dialogue in total." His feverishly bitten nails are almost non-existent as he continues. "Its a great opportunity for you though. You just need to stand around and look shapely in a costume which often risks exposing your labia...." His voice drops as he mumbles, almost incoherently, the critical conclusion to his sentence: "....outside Auschwitz."

A silence envelopes the room as the reality of what the role entails, and the multiple problematic aspects of the pitch, dawns on all involved. As an apoplectic Munn prepares to fire her agent, he desperately summons forth his final Hail Mary - a plea to remember the vitriol she inspires in troubled nerds who genuinely state that she's appropriating 'their culture'. "At the very least you'll be able to piss off a lot of angry, emasculated geeks again." Munn, I imagine, signs the contract with the enthusiasm of a six-year old unwrapping presents on Christmas morning. It matters not how degrading and pointless her role is - Munn leaves the meeting with a heavily pertruding wallet and a conclusive victory over the array of entitled, whiny nerds who can now add to their array of injustices the world has cruelly served against them (see also: the Ghostbusters reboot, people wanting Captain America to be gay / Captain America joining Hydra ).

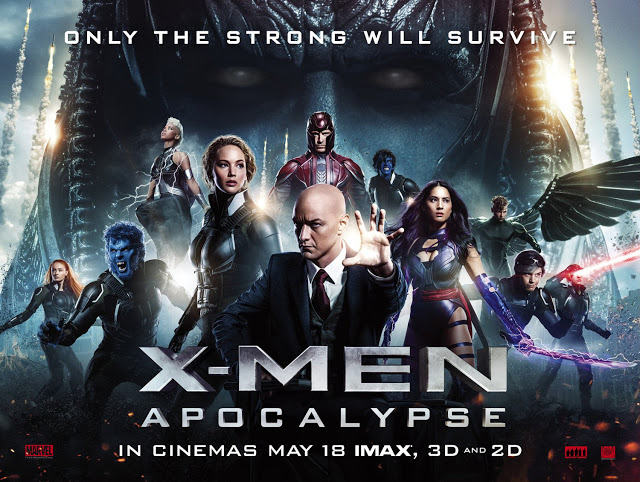

Ultimately, in case the opening three paragraphs did not make you sufficiently aware, Munn's role as Psylocke is entirely expendable. To excise the part from the script would have no major bearing on what exists of a narrative here. This is the problem in general for X-Men: Apocalypse - there's no real character arcs for anyone to experience (bar one overly familiar one we've witnessed over and over throughout the franchise's multiple installments), as superhero abilities, rather than discernible personalities, become the backbone of the movie. This, in however you prefer to rate the quality of a motion picture, is simply not good. In today's market, though, it doesn't need to be.

Singer's film, as is the trend of modern comic book big screen outings, is populated by a large number of characters but, unlike The Avengers for example, there's no one for us to relate or care about. The multiple vignettes which introduce us to our heroes, and indeed villains, often appear to be included for no purpose other than to take up time - and boy does time drag. The experience of watching this superhero film felt like how I imagine Quicksilver would experience viewing the entirety of Shoah. Yet, as we observe Quicksilver himself in the film's most tedious and derivative sequence, it is possible to entirely understand exactly why X-Men: Apocalypse is such a terrible viewing experience.

Today's audiences are largely not that interested in stories or storytelling and even less so in originality. Instead, all that we collectively aspire to is a big-screen regurgitation of things which we already recognise. That Quicksilver replicates a set-piece from a previous installment of X-Men is not a worry for most - there's a sense of comfort in recognition. We may have already seen Magneto flip from bad to good to bad again multiple times in multiple episodes of the franchise too but, alas, this is something we never tire of. We welcome tedious repetition. Our post-modern appetites to avoid anything new, and to have our culture curated to us as patchworks of things that came before, are satiated in superhero films. These features are untroubling, we already understand what will happen, and allow us to remain in a state of arrested development - in this respect, they're conservative movies which allow us to exist in a place and time of contentment rather than contempt.

Scrolling through forums and message boards, its impossible not to come across waves and waves of "comic book fans" who rejoice in the fact that characters and plots from the source material are reproduced on-screen. Coherence or reason matter not. All that is important is fidelity to comic books once read. In X-Men: Apocalypse, this trend reaches its nadir - this is a tick-box exercise market tested for entitled geeks to the point where any soul and enjoyment have been removed. The studio knows it doesn't even need to make a good film as character recognition alone will result in phenomenal box office regardless of how much general viewers abhor the experience (see: Batman v Superman for example).

These movies allow us to return to the state of a four year old asking for the same bed-time story night after night and woe betide if any details are changed. Any sense of alteration, of originality, is met by whining fan-boys who bray and cry like the aforementioned four-year olds. I do not argue, here, that movies are keeping us juvenile and but, rather, the opposite - our spoilt entitlement is keeping movies juvenile. It is the public who leads the market in this respect and not vice versa. We're given films like this because we deserve them - the irony is that comic book geek entitlement is slowly strangling the "culture" they profess to love by embracing, rather than rejecting, the substandard. And that, perhaps more than Olivia Munn's labia in Auschwitz, is the upsetting thing here.

No comments

Post a Comment