Earlier this week I interviewed a famous rock climber . What interested me the most, far more than details of his achievements, was not so much the things he had accomplished but why he aspired to achieve them in the first place – his inspirations. What motivated him to routinely risk his life for a sport? Why did he yearn so much to become the greatest in his field?

The details of character and motivation, to me personally, are far more fascinating than any achievement could ever be – it’s the human story, rather than the sporting achievement, which will always provoke emotion and create folklore. The power of Rocky, for example, stems not from one man’s ability to bludgeon his opponent into unconsciousness but, rather, in our protagonist’s stoic refusal to give up in the face of all logic; his determination to succeed which transcends the physical. Rocky is only an interesting character as he equates his worth as a human being with his stubborn inability to submit and, in the process, takes gruesome beatings in his belief he can achieve salvation this way. As illustrated, character will always be more important than any sporting achievement alone could ever be.

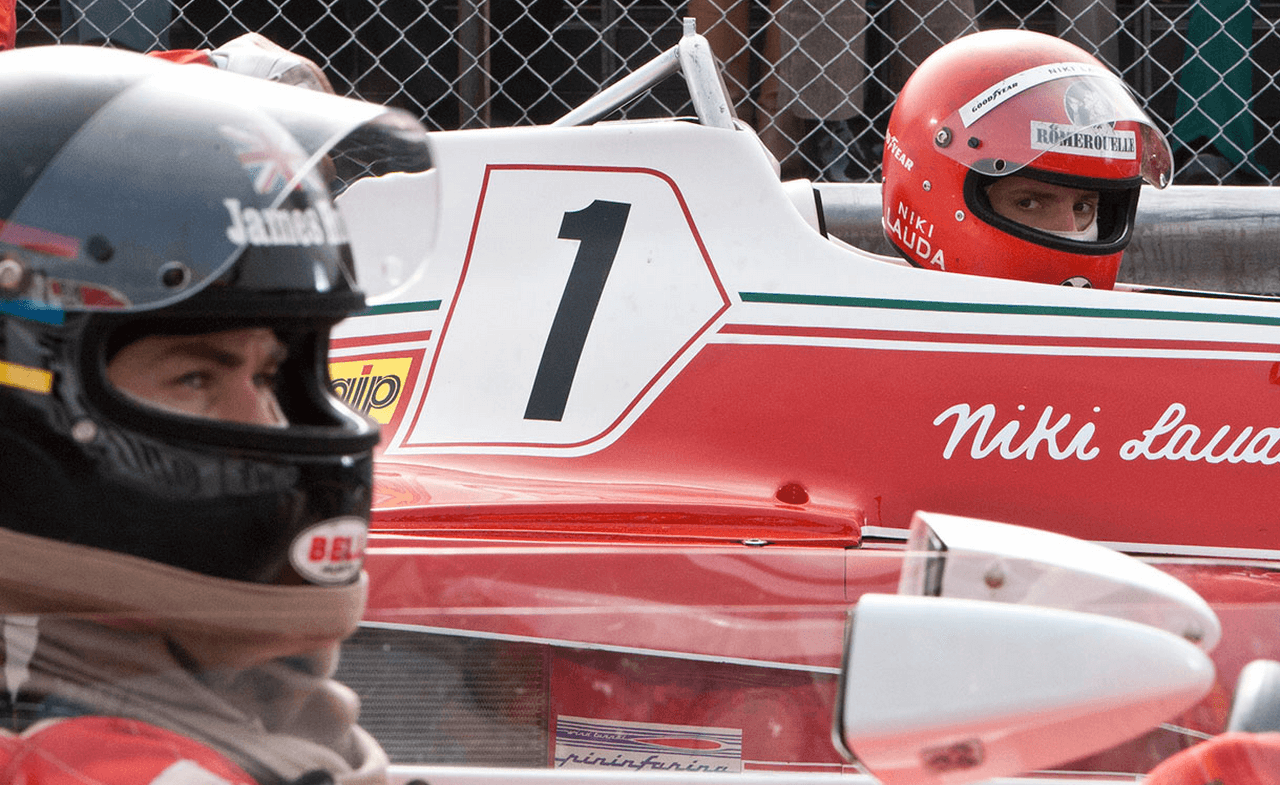

This thought sprung to mind whilst watching Ron Howard’s latest feature Rush – a big budget biopic of a brace of rival Formula 1 race car drivers. Images of machinery travelling at quick speeds, in and of itself, are not interesting; in order to succeed as a feature, Rush would have to get beyond the races and focus on the reasons for racing. What inspires these two young men to risk their lives for personal achievement? Why wouldn’t Niki Lauda (Daniel Bruhl) or James Hunt (Chris Hemsworth) be happy spending their days in a simple office job instead? Howard's film attempts to answer this but, sadly, skims surfaces rather than explore depths.

Fans of the 1990s comedy duo Lee & Herring may remember their tales of Ian Chalk and Ian Cheese – two men who are literally as different as chalk and cheese and who consequently don’t get along. Occasionally they do something which make each other realise that perhaps they are more similar than initially thought. This story was pitched, some twenty years ago, as a ludicrous and lazy sitcom idea no studio would pick up – here it has been re-appropriated as the central premise of a major cinematic release. It’s clear that Rush finds this hackneyed approach to storytelling very smart though; the symmetry of the two characters is a cause for insufferably smug celebration throughout the film's running time.

James Hunt, the British race car driver burdened with superstar good looks, seems less like a real person in Howard's Rush and more like an imagined character conjured solely for Zoo readers to live their lives vicariously through; fast cars, promiscuity, drink and parties. His is a charmed life for those who suffer from a paucity of existential ambition. We’re left in no doubt, very quickly, that Hunt is a stereotypical thrill-seeker – racing, and the dangers that come with it, represent adrenaline rushes and buzzes that give life meaning to what, under the surface, must be a very troubled soul. If this explains why Hunt drives, then what are we to make of Niki Lauda then? A man so diametrically opposed to Hunt in every way, it’s almost impossible to believe. He’s austere rather than wasteful, rational rather than emotive, sober rather than not – the two make clear, obvious rivals (a la Ricky Bobby and Jean Girard). And, oh, we never do find out why exactly Lauda decides to drive.

If this all sounds like Talladega Nights, it’s up to you to decide whether you believe the Will Ferrell film is a before it’s time satire or whether Ron Howard’s effort is a cliché ridden movie with no self awareness. Indeed, at points it seems that the director wants to tick off as many sports movie cliches as possible rather than concentrate on telling a worthwhile story - close-ups of tires, slow motion rain and a pained woman watching the climatic duel on a television far away all feature in a non-ironic fashion. As does perhaps the worst soundtrack of the year - a cloying saturation score which directs our emotions with the subtlety, and pleasantness, of neon signs. During races, distorted guitars kick in to signal excitement, strings tell us to feel emotional everywhere else. There was no single scene in this film which was not over-stated on every single formal level.

It should also be noted that Rush, for those of you who like that kind of thing, features fast cars. Lots of them. And they all go very fast.

No comments

Post a Comment