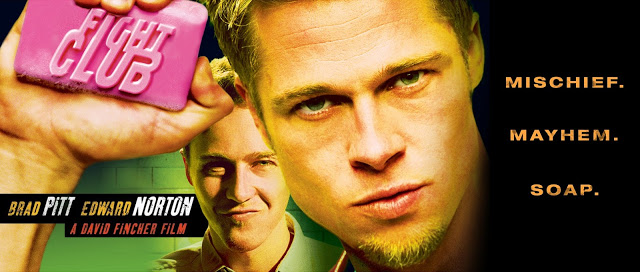

It is against this backdrop that Fight Club , David Fincher's cinematic adaptation of Chuck Palahniuk's novel, was released to critical acclaim. A grungy and atypically cynical assault on the banality of the modern world, Fight Club caused something of a sensation amongst a growing group of young adults, spiritually alienated and disenchanted by the emptiness of a society of mindless consumption developing around them - finally a film reflected the monotony and futility of everyday life, the Sisyphean nature of nine-to-five living. To provide context to just how revolutionary, not to mention achingly dangerous, the brash, bleak scepticism of Fincher's movie felt in 1999, it is worth noting that one of the pop culture events of the year prior to its debut was Geri Halliwell's chart-topping pseudo-Latin inflected single Mi Chico Latino.

A generation on, and with the benefit of hindsight, there are a number of questions we should be asking ourselves about Fincher's film, chiefly: was it actually any good? Or, to play devil's advocate, is Fight Club nothing more than a relic of its time, dating poorly like the cargo pants and orange lens sunglasses which were fleetingly in vogue as we counted down to the Millenium Bug inevitably wiping humankind off the face of the earth?

As Palahniuk's source novel approaches its twentieth anniversary, one of the most striking aspects of Fight Club is not so much how it satirically captured the spirit of the 1990s but, rather, the manner in which the tale successfully prophesied a growing, yet suppressed, toxic masculinity and corporate nihilism present in contemporary society. Whilst perhaps not the golden classic it was accepted as upon its reception, Fight Club is a strikingly pertinent movie worth revisiting if we are to understand many of the sicknesses at the heart of Western society.

* SPOILERS CONTAINED BELOW*

Toxic Masculinity

Perhaps the most obvious parallel between Fight Club and modern society is the role of aimless young men and their futile attempts at finding value in a world which rejects them. Capturing the zeitgeist twenty years before its emergence, Fincher's film presents us with Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) - a template to which modern men now aspire.In the 1990s, young men were too busy drinking lager, lager and ogling projections of Gail Porter to be overly concerned with their appearances - a dab of gel or a spray of Lynx Java to compliment their oversize Ben Sherman shirts and scuffed Kickers shoes would constitute the closest thing to narcissism 1990s man would know. In 2016, however, Western man no longer aspires to simply dress like Olympians but to look like them too. Creatine has replaced Pop-Tarts as a way to start the day whilst, to many, the measure of a man can be found in the circumference of their biceps rather than in any other measurable form. Durden, with his shredded six-pack and jutting hip bones has become an aspiration figure to many young men who have realised that, whilst its impossible to have any real agency within society, the one place to gain and demonstrate control is through their bodies.

It is this lack of agency which inspired the men of Fight Club to form their gang of violence and reflects a wider crisis of masculinity in a contemporary world. As modern men struggle with societal, and self-imposed, expectations new ways in which to express these frustrations are formed. Whilst Fincher's film satirically shows a rag-tag selection of men looking to find esteem and worth through their titular fight clubs, 2016 man is much more likely to find solace in body sculpting or through venting their spleen at "others" as part of the MRA (Men's Right Activist) movement.

Modern man is conflicted at what his role should be in society. Should they aspire to old-fashioned forms of masculinity - rugged, strong and designated provider for a family? Or, in an age where women are not widely expected to be exclusively stay-at-home wives, should men change with the times and consider it no longer emasculatory to be concerned with one's appearance, in touch with one's emotions and comfortable with women's equality in society?

It is in this schism Tyler Durden is born - an effeminate dressing pretty boy who, equally, fulfills older masculine tropes of strength and musculature also. His vocation, as a soap maker, speaks volumes of this impossible role he fills too - the end product, a largely cosmetic luxury, competes with the dangerous method in which it is produced; burning chemical compounds signify the potential peril which comes from composing such an item. That Durden is an imaginary character dreamed up by Fight Club's Narrator (Edward Norton) is entirely significant - following this impossible, imaginary idea of what a man can and should be leads nowhere but to destruction. Nothing good can possibly become of trying to live up to such ideals, suggests Fincher's film. Durden, rather than representing the height of masculinity then, acts as a metonym for all that is wrong with with modern man as the film shies clear from proselytising on how men should live in a world full of a myriad of contradictions.

Corporate Nihilism

Since Fight Club was released, the jobs market has changed considerably. Social Media Guru and Marketing Ninja are corporate positions real life humans put on their business cards. As capitalism needs to continually expand and, paradoxically, machines fulfill many of the roles humans used to command, traditional human-manned jobs are becoming obsolete. In their place, new, and ultimately meaningless, roles are created to make certain society stays well employed enough for capitalism to successfully function. The job titles which have been created in the post-Industrial age are entirely unnecessary in the grander scheme of things; they are inconsequential at best , painfully bullshit at worst. Would civilisation really collapse if many of our vocations simply vanished entirely overnight?Fight Club taps into modern corporate life and shows it for what it is - part Kafka-esque, part nihilistic nightmare. Fincher's film shows us the manner in which 40 hour, white collar working weeks not only bore and tire us but ultimately strip humans of any purpose in life both on an individual and society-wide basis. Famously, Norton's narrator lectures his audience about the futility of the manner in which society is laid out. We're asked to surrender all our time to accumulate money to buy things we neither want nor need to impress people we don't particularly like. In the years since Fight Club's release this truism has only grown in relevance; Apple, for example, has colonised many of our materialistic desires. No-one truly needs the latest iPhone to function in life yet, every release day, queues of desperate young status seekers surrender large swathes of money to replace perfectly functioning devices fashion has rendered as out of style. We've collectively become victims to our own consumption.

Fincher's movie viciously and vividly attacks our materialistic world with astounding precision - he shows how we've each become our own King Canutes, failing in our attempts to not be crushed by societal expectations to participate in endless, mindless consumption. Eat, sleep, buy, repeat. Despite the recent in vogue notion of "mindfulness", it would seem Western civilisation is becoming less, not more spiritual or philosophical. We're gladly resigned to committing our working hours to achieving nothing of note, worth or value and we surrender our dreams to fantasising about the latest clothes or technology we believe will make our lives better. They never do.

But that ending....

Yet, for all the positives that can be gleaned from the film for its social commentary, there are a number of elephants in the room when it comes to discussing Fight Club. Firstly, as a fully formed narrative, Fincher's film fails to sustain itself for the full duration movie's running time. As a piece of cinema, Fight Club is a grand, clever concept yet it is one without a satisfying conclusion. As the Narrator shoots himself in the head, and the world collapses around him, its tempting to imagine the ending must have been rush-written to pass a deadline. Of all the modern values the movie should have steered clear from subverting, the formation of a cohesive climactic story-line constitutes perhaps the most essential one. Fincher, it seems, realised that creating an ending for an elongated piece of vitriol was rather difficult so didn't bother.Another major problem with Fight Club is the deeply hypocritical ideology it represents. Yes, much of the film covertly and overtly warns us against the dangers of toxic masculinity yet, throughout its running time, Fincher glorifies and aestheticises it. Unlike the more intelligent examples of Robocop (1987) and Funny Games (1997), films which use extreme violence to appall us, Fight Club wants to have its cake and eat it; Fincher creates yet another Hollywood movie in which the cool, handsome hero physically dominates his foes to show his superiority. Its no surprise then, to hear anecdotes of young men inspired by the film to set up their own fight clubs in tribute - as the great Roger Ebert wrote : "a lot more people will leave this movie and get in fights than will leave it discussing Tyler Durden's moral philosophy". It is, after all, akin to a UFC event with the bonus of excellent cinematography and the foundations of a story arc. We're invited as an audience to simultaneously tut at the extreme violence we see whilst, simultaneously, applauding with respect and appreciation for the anti-heroes who carry it out.

No comments

Post a Comment