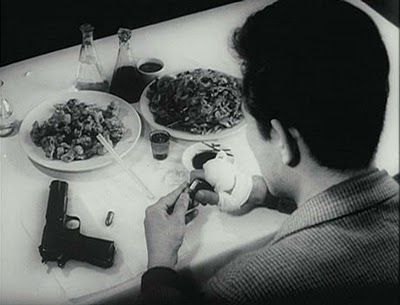

Filmed in a crisp monochrome, and often aesthetically reminiscent of Akira Kurosawa's early work such as Stray Dog, Yu Hyun-mok's 1961 Obaltan (Aimless Bullet) feels unrelentingly bleak and sterile in a profoundly haunting manner. The landscape Yu presents throughout the 108 minutes of his feature seem utterly devoid of hope and barren of compassion, a nightmarish yet gruesomely realistic world; it is no wonder the military government of the then young country may have felt an unease at the depressing way Obaltan viewed South Korea.

Whilst in the midst of a Cold War with it's neighbours in the North, the South's government must have felt threatened by any form of criticism of its model of capitalism, let alone an attack on its direction as saturated of joy as this - a film which peppers it's mise-en-scene with constant reminders of the country's history of being colonised (the ghosts of Japanese occupancy are in plain view), and equally (through the iconography of Coke and the presence of prostitute-frequenting American GIs) with the nation's current status as "hosts" to American troops and the Western way of living.

Whilst in the midst of a Cold War with it's neighbours in the North, the South's government must have felt threatened by any form of criticism of its model of capitalism, let alone an attack on its direction as saturated of joy as this - a film which peppers it's mise-en-scene with constant reminders of the country's history of being colonised (the ghosts of Japanese occupancy are in plain view), and equally (through the iconography of Coke and the presence of prostitute-frequenting American GIs) with the nation's current status as "hosts" to American troops and the Western way of living.

The tale focuses on the life of an honest accountant who, rather than get his cavity fixed, spends his money looking after his wife, two young children, a brother who won't work and a mentally ill mother who live together in squalor. His sister prostitutes herself out to foreigners to add to her coffers and, to a family who have always held themselves to high standards, this does not seem like just rewards for their honesty and integrity. It's a bleak indictment of Rhee Syng-man's Korea and the Seoul of Olbatan is far from the sprawling metropolis it is today. Rather, its broken, wilting and trying to figure how to re-calibrate itself after the horrors of the still recent civil war - a state reflected, rather pertinently, by the family who act as the leads in Yu's film. It's the story of the new nation of South Korea looking at itself in the face and facing disappointment at not seeing great beauty staring back - in fact, the reflection is something entirely, and grotesquely, unrecognisable. Obaltan, in this respect, mirrors the nation's struggle with coming to terms with itself in the aftermath of a half century clouded by colonisation and civil war.

The movie bleeds sympathy for it's richly painted every man characters, not least the far from perfect unemployed former soldier who is unable to get a job despite the fact he had literally given his flesh and blood in the name of his country - "Young hero! Brave soldier! These were my qualifications!" The struggles in war have hardly led to glory or reward at home and, as such, he becomes tempted with amoral ways of making money for himself. When a fair hand hasn't been dealt in life, why should players stick to the rules? It's easy to be moral and conscientious from a position of privilege, much harder when every day is a struggle. When you've had bullets tear through your body whilst protecting your country, bitter sores are likely to fester and grow in the mind when the same nation has little to offer in return for your sacrifices.

Clearly cut from the same cloth as Kim Ki-young's The Housemaid, this early 60's movie is a subversive look at the young country from where it was born, subtly peering at the inequalities of the place and brimming over with fear as to fate of nation. Unlike Ki-young's flamboyant Housemaid, however, Yu's movie boasts realism in its pallet (not dissimilar to European neo-realism a la Bicycle Thieves) through naturalistic performances and a lack of contrived stylisation; austerity runs energetically through Obaltan's veins.

* Obaltan (also known as Aimless Bullet or Stray Bullet) is widely referred to as one of the greatest Korean films ever made and, as such, has been made

available to watch in it's entirety for free on Youtube

(alongside a whole host of equally important features) by the

Korean Film Archive

in an incredibly forward thinking move from the organisation.

As Obaltan is currently out of print, opportunities to see such a culturally significant movie would be next to none for the majority of individuals (particularly in the non-Korean speaking world) and, as such, making the feature available for public consumption is a truly magnificent declaration of the democritisation of art. Yu managed to release his dour vision not long before Rhee et al clamped down on his country's artists with censorial zeal. It's lucky that this film sneaked out when it did and it's even luckier that Korea today is a forward thinking country who have gone to great lengths to protect its cinematic heritage.

As Obaltan is currently out of print, opportunities to see such a culturally significant movie would be next to none for the majority of individuals (particularly in the non-Korean speaking world) and, as such, making the feature available for public consumption is a truly magnificent declaration of the democritisation of art. Yu managed to release his dour vision not long before Rhee et al clamped down on his country's artists with censorial zeal. It's lucky that this film sneaked out when it did and it's even luckier that Korea today is a forward thinking country who have gone to great lengths to protect its cinematic heritage.

No comments

Post a Comment